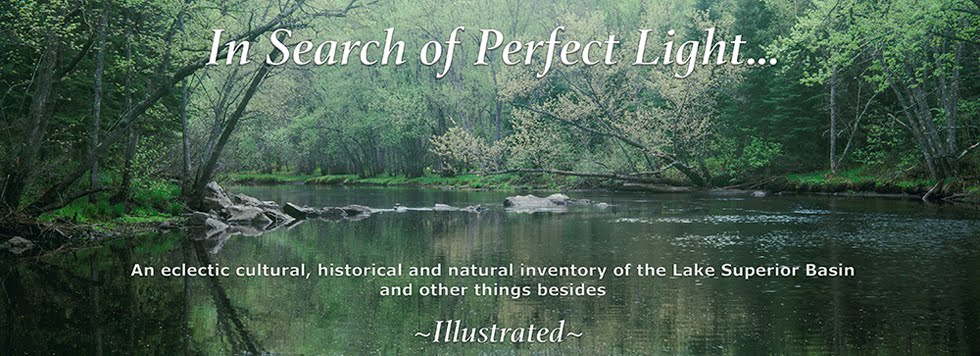

Eventually,

all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. The river was cut by

the world's great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time.

Spend enough quality time wandering the wilderness and occasionally, a specific

place might become sacred. For me, one of those is the short stretch of woods

through which the Presque Isle River on its way to Superior cuts through hard rock at

what we call Yondota Falls.

I know exactly when that started.

It was a misty autumn day when as young adventurers Johnny, Heather & I cooked lunch upon a carpet of damp moss covered in pine needles shaded by gnarled evergreens. But for the turbulent river below, all the world was at peace.

A bald eagle floated by just overhead, come down from near extinction to take a closer look at the trio of humans gathered in curious ceremony atop this slippery, sheer rock wall:

It was a misty autumn day when as young adventurers Johnny, Heather & I cooked lunch upon a carpet of damp moss covered in pine needles shaded by gnarled evergreens. But for the turbulent river below, all the world was at peace.

A bald eagle floated by just overhead, come down from near extinction to take a closer look at the trio of humans gathered in curious ceremony atop this slippery, sheer rock wall:

Or maybe it just smelled the meat cooking.

In any event, the place hooked me. My connection to it deepened

through the decades until now, to the extent I recognize the word, it's sacred

to me.

The first image of mine to ever hang in a gallery was of Yondota rock. In truth a pretty crappy photo, the gallery owner undoubtedly credited

my enthusiasm but also recognized incipient value in my vision.

Most every person who ever visits merely stands on the stone to watch the water slip by and admire the general scenery, before heading back to the road and going on their way. Perhaps to the next set of waterfalls on the traveling list.

Most every person who ever visits merely stands on the stone to watch the water slip by and admire the general scenery, before heading back to the road and going on their way. Perhaps to the next set of waterfalls on the traveling list.

Instead, I'd seen the rock. And it's

Yondota rock that keeps drawing me back.

In a wilderness almost entirely reconstructed of second or third growth

forests and even the trees aren't the same sorts of trees there used to be, sites of authentic ancient resonance are rare. Sanctuaries hidden in deep woods where echoes

of human history are wholly absent free the staggering resilience of life on

earth to be manifest, and whispers older than memory can be heard plain.

These are landscapes made of lasting interrelationships fostered by complex organic symmetries predating humans by an extra wide margin. Having lasted so long the sites will likely outlive us since there, daily living retains natural integrity.

Inhospitable to us as the terrain may truly be, it's still infinitely more viable than we. At the very least, that should give us pause.

Inhospitable to us as the terrain may truly be, it's still infinitely more viable than we. At the very least, that should give us pause.

Born of vulcanism and in middle age broken by glaciers, the rock remembers before

there was life on earth.

In our time, periodic high water sweeps the land clean. The river falls and off placid pools of rich fresh water trapped by inviolate stone, life flourishes. Then the river rises again.

What's hearty enough to survive until the flood recedes, does.

What's hearty enough to survive until the flood recedes, does.

This ancient landscape would slough modern humanity off and deliver us in pieces downriver

for Superior to disperse. We cannot live there. Happily, that leaves the most

permanent wilderness to those who can.

Today when unintended consequence promises another great flood and what to do about that before it wipes us away is a Sisyphean riddle hiding a Gordian knot, we must draw strength that Yondota still exists. Because at this spot in the forest along the Presque Isle River, the natural relationship

between water, stone and land that enables terrestrial life goes on unimpeded.

It's there to see. One need only look.

It's there to see. One need only look.

At Yondota Falls, moment frequently combines with light and in a

backwoods pool one might capture the Earth's past, its present and perhaps even the

future in a single glance.

To me, that's entirely sufficient evidence to accept the place as sacred.